Arthur Caplan Backs Advance Directives to Refuse Spoon-Feeding in Dementia Care

A controversial bioethics debate is gaining national attention—should caregivers be required to honor advance directives that instruct them to withhold spoon-feeding and oral hydration from patients in late-stage dementia?

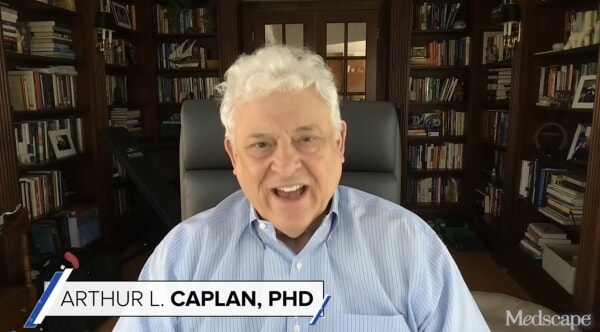

Now, one of America’s most cited bioethicists, Dr. Arthur L. Caplan, is taking a public stand in support of such directives. Caplan, founding head of the Division of Medical Ethics at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, argues that spoon-feeding in advanced dementia care should be treated as a medical intervention—and that competent adults should have the legal and ethical right to decline it in advance.

We routinely honor directives to withhold or withdraw medical treatments. Spoon-feeding is no different if it conflicts with the patient’s clearly expressed prior wishes. — Dr. Arthur L. Caplan in a commentary for Medscape (Medscape, Aug. 2025).

Caplan’s position has sparked sharp debate, with supporters framing it as a matter of personal autonomy and dignity, while critics warn it could lead to unintended suffering or abuse.

Feeding: Comfort or Medical Care?

Currently, U.S. law generally distinguishes between medical treatments (such as feeding tubes or ventilators, which can be refused through an advance directive) and basic care (like oral spoon-feeding), which is typically seen as comfort care and more difficult to refuse legally.

Caplan challenges that distinction.

Feeding and hydration by hand can be just as intrusive and against someone’s wishes as a feeding tube, depending on the context. If a person documents refusal clearly while still mentally capable, we ought to respect it. — Dr. Arthur L. Caplan.

He acknowledged the emotional weight of these decisions, especially for family members and professional caregivers who may interpret eating behavior—such as opening the mouth or swallowing—as signs the patient wants to eat.

There is an understandable reluctance to withhold food. But this is about respecting the rights of the person who once had full capacity. Their voice should still count. — Dr. Arthur L. Caplan.

Critics Push Back: Where’s the Line?

Some experts in elder care and ethics remain cautious.

Some experts in elder care and ethics remain cautious. Dr. Tia Powell, director of Montefiore‑Einstein Center for Bioethics, has emphasized the ethical complexity of the issue—specifically the distinction between refusing life‑support like ventilation and refusing a meal.

She has publicly cautioned that interpreting nonverbal behavior in dementia patients is difficult, and that caregivers should avoid assuming that passivity implies consent or that refusal of food automatically preserves dignity

Interpreting nonverbal behavior in dementia is hard. We must avoid assuming passivity equals consent—or denial of food equals dignity.

Legal scholars also raise concerns. In some states, feeding—even by hand—is considered a basic human right under elder protection statutes. If advance directives to refuse feeding are honored, questions about interpretation, implementation, and family disagreement could quickly surface.

A Growing Family Caregiver Crisis

The ethical dilemma isn’t happening in a vacuum. It comes at a time when family caregivers are overwhelmed, under-resourced, and increasingly responsible for complex decisions.

More than 63 million Americans are now providing unpaid care to older parents, spouses, or other loved ones—up from 53 million in 2020. That care often includes feeding, dressing, bathing, and even administering medications.

Many are helping loved ones with dementia—one of the most demanding caregiving roles. The emotional toll is steep, especially when navigating end-of-life choices like feeding refusal.

Family often must step in for a lack of funds or Long-Term Care Insurance.

People With Dementia Can Still Have a Quality Life

While Caplan’s comments address the late stages of dementia, many health experts caution against overly grim assumptions about earlier stages.

People with mild cognitive impairment or early-stage dementia can still lead full, meaningful lives with the right support systems in place. — Dr. David Reuben, chief of geriatrics at UCLA Medical Center, in an interview with The New York Times.

Studies confirm that people in the early or moderate stages of dementia often maintain emotional well-being, social connection, and awareness of their surroundings. Structured routines, memory aids, caregiving support, and long-term care services make a measurable difference.

Care isn’t just about prolonging life. It’s about enriching it.” Even in moderate Alzheimer’s, people can find joy, especially in familiar settings with empathetic caregivers. — Dr. Catherine Loveday, a neuropsychologist at the University of Westminster, quoted in The Times U.K.

Long-Term Care Planning

This debate reinforces why early long-term care planning is essential.

If you or a loved one wants to include feeding directives in your care plans, consider these steps:

- Be specific: Include clear language in your advance directive about what types of feeding you want or reject—and under what conditions.

- Communicate: Talk to family members, physicians, and your designated healthcare proxy about your values and choices.

- Explore funding: Long-Term Care Insurance can help pay for quality care in settings that support autonomy and dignity—whether at home or in memory care facilities; however, an LTC policy must be purchased when you have reasonably good health, often in your 40s through 60s.

Use the LTC News Caregiver Directory to search for quality caregivers a long-term care facilities to provide a loved one with a better quality of life.

Matt McCann, a leading expert in long-term care planning, says he has seen how those with dementia can still have a good quality of life with proper care.

I’ve seen that even with a dementia diagnosis, people can live with dignity and purpose—if they receive the right kind of care. Quality of life doesn’t disappear with memory loss. It’s preserved through compassionate support, structured routines, and access to long-term care services tailored to the individual. — Matt McCann.

Final Thoughts: Autonomy, Compassion, and Conversation

Many say that Dr. Caplan’s position may push the ethical and legal envelope, but the underlying issue is timeless: how to honor a person’s values when they’re no longer able to speak for themselves.

It’s not just a question of law—it’s one of love, communication, and planning.

Questions to Consider When Writing an Advance Directive:

- Do you want to refuse spoon-feeding or only artificial nutrition?

- When should your directive take effect?

- Who will interpret and enforce your wishes?

- Have you discussed this with your healthcare proxy?

Before you get older, being prepared and having a discussion with loved ones should be high on your agenda.